When you start investing, you usually know it won’t make you rich overnight. You expect it to be gradual, steady, maybe even slow. What most people don’t anticipate is just how slow the early phase can feel.

For several years, your portfolio will grow, but not in a way that feels meaningful. Most of the growth comes from the contributions themselves. Market swings may seem larger than your gains. The total value increases, but slowly enough that it can feel like little progress is being made.

This is often when doubt starts to appear. You might wonder if your strategy is wrong or whether investing is worth it. Usually, it isn’t a question of doing something wrong — it’s simply the early stage of compounding.

Charlie Munger summarized this phase bluntly:

The first $100,000 is a bitch.

It’s not a pep talk. It’s an observation about how capital behaves when it is still small.

Why early investing feels slow

When your portfolio is small, even a strong percentage return doesn’t move the needle in absolute terms. Early gains are dominated by your own contributions. This makes the first years feel tedious, because effort is high while the return is low.

It’s not a sign that compounding isn’t working — it’s just too early for the math to have a visible effect. Time is doing most of the work quietly, without providing immediate rewards.

How the first €100,000 compares to later growth

To see why this phase feels slow, consider a straightforward example:

€1,000 invested every month

8% average annual return (AAR)

No changes in contributions or strategy

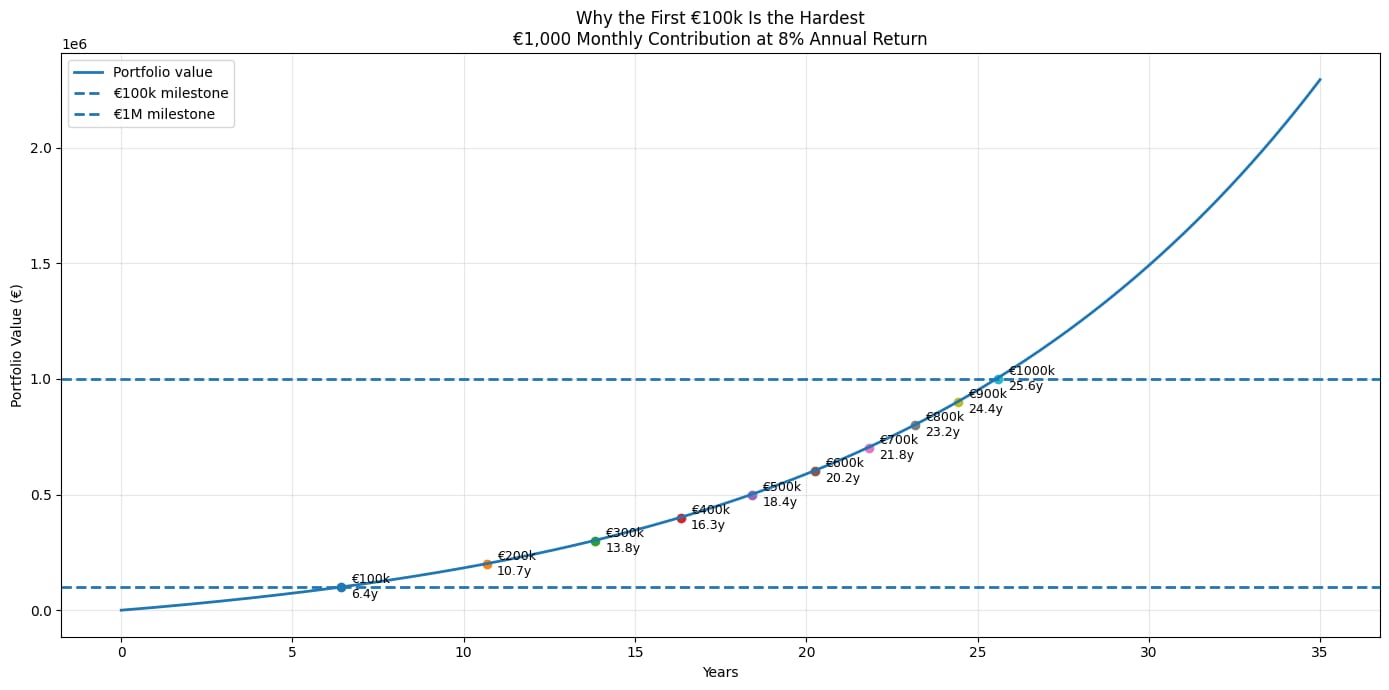

When we plot the portfolio value over time, the pattern becomes clear.

Why the First 100K is the Hardes - EUR 1K Monthly Contribution @ 8% AAR

For the first few years, the curve is relatively flat. Growth comes primarily from your monthly contributions; the effect of returns is still modest. Only after the base has grown sufficiently does compounding begin to noticeably accelerate the portfolio value.

Time needed for each €100,000

Using the same assumptions, here’s how long it takes to reach each €100,000 milestone:

Milestone | Total years needed | Years for next €100k |

|---|---|---|

€100k | 6.4 | 4.3 |

€200k | 10.7 | 3.2 |

€300k | 13.8 | 2.5 |

€400k | 16.3 | 2.1 |

€500k | 18.4 | 1.8 |

€600k | 20.3 | 1.6 |

€700k | 21.8 | 1.3 |

€800k | 23.2 | 1.3 |

€900k | 24.4 | 1.2 |

€1,000k | 25.6 |

Notice the pattern: the first €100,000 takes the longest of any individual €100,000 segment, and each subsequent €100,000 requires less time. The absolute growth remains slow at first, which explains why it feels like a long climb. After about €200,000–€300,000, momentum starts to become more visible, and progress begins to feel faster.

Why many investors struggle early

The slow early phase is why many investors give up. Six years of steady investing can feel like a long time, especially when the portfolio doesn’t yet provide a sense of momentum. Drawdowns seem larger relative to the portfolio, and gains are modest in absolute terms.

As a result, people may reduce contributions, change strategies, or stop investing altogether — just before the dynamics start to shift. Ironically, quitting often happens right before compounding begins to accelerate visibly.

Once a portfolio reaches a certain size, returns begin to matter more than contributions. Market volatility feels less threatening. Growth becomes largely self-reinforcing.

What the €100,000 milestone actually represents

The €100,000 mark is not symbolic. Its importance is mathematical.

Below this level, outcomes are dominated by behavior: consistent saving, discipline, and time in the market. Above it, the portfolio itself begins to generate significant returns, and growth becomes more dependent on capital than contributions. This is when risk management, allocation, and other strategic decisions start to have more impact.

The early phase is essentially a test of patience: sticking with a strategy long enough for compounding to become noticeable.

A Quantigo perspective

At Quantigo - I try to approach investing through data, risk, and behavior rather than narratives. The conclusion from this example is straightforward:

The hardest part of investing is staying consistent through the early years.

The first €100,000 is slow, but necessary.

Persistence pays off once compounding starts to dominate growth.

Charlie Munger’s comment was not meant to discourage you. It was an observation: the first €100,000 takes longer than the next individual segments. Those who make it through experience the point where investing begins to “work” in a more visible, compounding way.